Three questions to...

Lara Puhlmann and Esra Al, this year’s winners of the Otto Hahn Medal.

The Max Planck Society honours young scientists and researchers each year with the Otto Hahn Medal for outstanding scientific achievements. This year, Lara Puhlmann and Esra Al from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences (MPI CBS) won two of the coveted awards.

Every year, the Max Planck Society honours some of the outstanding achievements of its doctoral students and postdocs at its annual meeting with the Otto Hahn Medal. Like few others, Otto Hahn embodied scientific excellence and the pursuit of progress on a personal and societal level throughout his life. As President from 1946, he led the successful transformation of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society into the Max Planck Society.

This year, two scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences (MPI CBS) received two of the coveted awards: Lara Puhlmann, who studies how mental training of meditation and psycho-social skills affects stress, and Esra Al, who wants to understand how our heart influences the perception of our brain. In three questions, they explain what it's all about.

Lara Puhlmann, former Research Group Social Stress and Family Health

Your dissertation has just been awarded the Otto Hahn Medal. What makes your research so special?

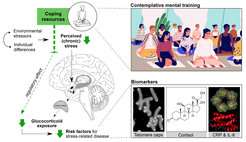

My work was awarded for tackling a socially highly relevant question - How can we live healthy and stress-free lives? - in a particularly interdisciplinary way. Specifically, I investigated how mental training of meditation and psycho-social skills affects physiological biomarkers of stress and stress-related illness. Through the training, subjects cultivated mindfulness-based attention, positive affect, compassion, and perspective taking, among others. The results show that all these different training elements reduced an important physiological indicator of long-term stress, deposits of the stress hormone cortisol in the hair, by an average of 25% after up to 9 months. Other biomarkers, such as inflammatory proteins or telomere length, a measure of our biological age, remained largely unchanged.

So I was able to show that pure mental training improves our stress physiology in the long term. Only healthy participants from the general population were included in our intervention study. The fact that physiological stress reduction was achieved even in this not exceptionally stressed group suggests that joint training of psycho-social skills, mindfulness and meditation could be suitable for the prevention of stress-related diseases such as depression. At the same time, my work also illustrates the limits of the positive training effects and shows which biological systems could apparently not be influenced in a preventive way. What was special about my work was therefore also the methodological breadth that is necessary to look at health effects in this way in a more holistic and systemic way.

Overall, and given the often serious structural and social determinants of stress levels and health, it is remarkable that mental skills can nevertheless strongly influence physiology - and that these skills also seem to be malleable, with direct effects on our physical condition.

What is your motivation to work on this topic?

I am fascinated by how our psyche can influence our physical well-being, and our physiology our mental well-being. In stress research, this close interplay between body and mind is particularly clear: psychosocial stressors, such as time pressure at work, trigger an initially adaptive physiological stress response. In the long run, however, this can lead to psychological disorders such as depression, as well as physical ailments such as cardiovascular disease. At the same time, stress is omnipresent, as its facets range from everyday annoyances to structural disadvantages. In my work, I am therefore also motivated by the societal relevance of a holistic, biopsychosocial perspective on health, and especially the new ways of preventing stress-related diseases that this offers.

The prize-winning thesis is in the bag. What’s next?

Meanwhile, as a postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Resilience Research, I am investigating the question of which factors contribute to people reacting resiliently to stressful experiences, i.e. maintaining or quickly regaining their psychological well-being. Thus, in addition to individual psychological and physiological predispositions, I also look at the interaction with external stresses and life events. I am particularly interested in how we can measure the psychological components of stress resilience more objectively and accurately in order to improve their integration with physiological measures and behaviour. I am currently investigating whether so-called digital biomarkers such as voice pitch and facial expressions can be used as more objective indicators of psychological well-being. Next year, I will also pursue this question as a fellow in the College for Life Sciences at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin.

Esra Al, Department of Neurology

Your dissertation has just been awarded the Otto Hahn Medal. What makes your research so special?

We consider the brain to be the center of our being, governing our senses, movements, thoughts, and memories. However, it is important to recognize that the brain is intimately connected to the body, and this connection operates in both directions. The body's internal organs play a crucial role in communicating essential information to the brain, profoundly influencing how we perceive and interact with the world. Recent studies have shed light on the remarkable impact of the heart's activity on our subjective experience, extending far beyond its traditional role in regulating bodily functions and blood flow.

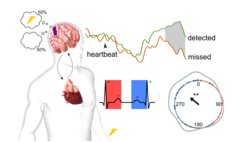

In my research, I investigated the intriguing connection between cardiac signals and somatosensory perception through a series of experiments. First, we discovered that the timing of stimuli in relation to the systolic or diastolic phase of the cardiac cycle influenced participants' ability to detect and locate them. Surprisingly, perception was reduced during systole, the phase when the heart contracts and pumps blood into the body. Additionally, we observed the suppression of a specific brain activity component, the P300, associated with consciousness during systole. During this phase, the brain predicts that pulse-related bodily changes are not indicative of external stimuli, helping us filter out constant awareness of our pulse. However, this mechanism can result in the overlooking of weak stimuli coinciding with systole, despite their actual presence. These findings highlight the heart's significant role as a modulator, impacting our perception and processing of sensory information.

Moreover, we uncovered another intriguing effect of the heartbeat on perception: When individuals had higher neural responses to their heartbeats, they exhibited reduced detection of upcoming stimuli. This effect can be attributed to a shift in attention from external environmental signals towards internal cardiac signals. Essentially, a strong heartbeat-evoked response appears to reflect a "state of mind" in which we become more attuned to the functioning of our inner organs, such as blood circulation, while simultaneously being less aware of stimuli from the external world. These findings highlight the intricate interplay between the heart and the brain, underscoring their profound impact on our perception of the surrounding environment.

Understanding the mechanisms of interaction between the heart and the brain is crucial for unraveling the mysteries of conscious perception. By investigating the effects of cardiac signals on somatosensory perception, my research contributes to our understanding of the intricate relationship between our bodily processes and our subjective experience.

What is your motivation to work on this topic?

My motivation to work on this topic stems from a deep fascination with the ever-changing nature of our perception. Despite being exposed to the same external stimuli, our subjective experience can vary significantly. While neuroscience research traditionally focused on the brain, recent studies have unveiled the crucial influence of our body, including the intricate relationship between our heartbeat and perception. This realization has sparked my curiosity and propelled me to explore how the dynamic interplay between the body and brain contributes to our conscious experience. I am driven by the desire to unravel the mechanisms through which changes in our body and brain impact our perception of the world, ultimately shaping our conscious reality.

The prize-winning thesis is in the bag. What’s next?

Currently, as a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University, my focus remains on delving deeper into the fascinating realm of how respiratory and cardiac signals contribute to shaping perception. Specifically, I am utilizing intracranial neural recordings to unravel the intricate relationship between these bodily signals and the subjective experience of perception.

Additionally, my research endeavors extend to investigating the correlation between body-brain coupling and changes in anxiety levels, with a particular interest in exploring whether this coupling is mediated by arousal. By unraveling these connections, I aim to shed light on the underlying mechanisms that govern our conscious experience and expand our understanding of the complex interplay between our body, brain, and subjective reality.

Through my continued research and exploration, I am driven to uncover new insights into how changes in our body and brain influence our perception of the world, ultimately shaping our conscious experience. By pushing the boundaries of knowledge in this field, I hope to contribute to the broader understanding of human cognition and pave the way for potential applications in areas such as mental health and well-being.