Learning a second language is transforming the brain

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig have unearthed fascinating evidence that the brain undergoes important changes in wiring when we embark on the journey of learning a new language in adulthood. They organized a large intensive German learning program for Syrian refugees and studied their brains using advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), uncovering dynamic modulations in the wiring of crucial language regions that enabled them to communicate and think in the new language.

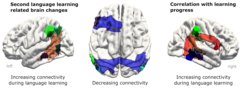

Over a six-month period, Xuehu Wei and the research team led by Alfred Anwander and Angela Friederici, meticulously compared the brain scans of 59 native Arabic speakers engaged in intensive German learning. By taking high-resolution MRI images at the beginning, middle and end of the learning period, the researchers deciphered changes in connectivity between brain areas using a technique called tractography, which allows the reconstruction of neuronal pathways. These images showed the strengthening of white matter connections within the language network, as well as the involvement of additional regions in the right hemisphere during second language learning.

“The connectivity between language areas in both hemispheres increased with learning progress”, explained Xuehu Wei, first author of the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). “Learning new words strengthened the lexical and phonological subnetworks in both hemispheres, especially in the second half of the learning period, the consolidation phase.” Intriguingly, the study also revealed a reduction in connectivity between the two hemispheres, suggesting a crucial role of the corpus callosum – a bridge-like structure that connects the left and the right side of the brain. This reduction suggests that a decreased control of the language-dominant left hemisphere over the right hemisphere during second language acquisition, feeing up resources in the right side of the brain to integrate the new language.

“The dynamic changes in brain connectivity were found to be directly correlated with the increase in performance in the language test of the Goethe-Institute,” emphasized Alfred Anwander, the study’s last author. “This underlies the importance of neuroplastic adaptations of the network to process the newly learned language and the use of regions in the right hemisphere that were previously untapped for language processing. More generally, this study sheds light on how the adult brain adapts to new cognitive demands by modulating the structural connectome within and across hemispheres.”

As one of the first large and well-controlled projects documenting changes in brain connectivity during second language learning, this research may pave the way for a deeper understanding of how first and second languages are learned and processed. Beyond language acquisition, the study opens new avenues for understanding brain function and the effects of experience-dependent structural plasticity. In addition, the language learning project has implicitly opened the door for Syrian refugees to integrate into German society.